The Katherine Swynford Society runs two quarterly writing competitions – one biographical the other fictional. Their website states that:

The Katherine Swynford Society runs two quarterly writing competitions – one biographical the other fictional. Their website states that:

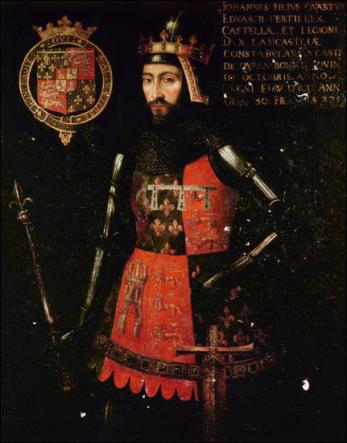

The main characters may be a mixture of the following: ancestors, contemporaries or descendants of John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, and his three wives; Blanche of Lancaster, Constance of Castile and Katherine Swynford. Minor characters may include any members of John of Gaunt’s entourage in the Duchy of Lancaster. The aim of the competitions is to promote and stimulate interest and research into the life of Katherine Swynford and the late Medieval period.

http://www.katherineswynfordsociety.org.uk/short-story-competition.html

There certainly isn’t a shortage of ancestors or descendants to write about. I shall peruse them in due course. In the meantime I’ve become intrigued by the “minor characters.” The English Historical Review Vol. 45, No. 180 (Oct., 1930) contains an article about the way that John of Gaunt packed the Good Parliament of 1376 with his supporters. The writers goes on to make analysis of the number of paid Lancastrians in the twelve parliaments between 1372 and 1382 (pp. 623-625.) It turns out that from the one hundred and twenty-five knights he identifies on John of Gaunt’s payroll that thirty did a stint as a member of parliament during the decade identified.

The reason that the article could be written and the Katherine Swynford Society are able to include individuals from John’s retinue so specifically is that amongst Gaunt’s documents is a list of his retainers. He is the only medieval magnate where such a list exists (although of course it doesn’t mean that other lists won’t be discovered languishing in archives or being reused for backings to other documents). The list covers the period 1379 to 1383 – although it appears to be an amalgamation of knights from a more wide ranging span that’s been collated and filed at this point. It exists because many of the knights and squires in John’s service were required to sign a contract or as it was then called an “indenture of service.” The indenture identified behaviours, duties and rights for times of peace and for times of war. These documents were then enrolled in chancery where they were confirmed by the king: in this case Richard II. Bean contains a detailed analysis of the list. He notes that ten knights have “cancelled” by their name. Three of them were dead so I’m left wondering about the other seven! In total there were eight-five knights and eighty-five squires – some of them were cancelled as well but rather more cheerfully this appears to have been because they were promoted.

Other sources of information about John’s retinue come from his account books which is the main source for identifying Philippa Chaucer and other women including Katherine Swynford who were in the pay of Lancaster at one time or another. By chance several of Gaunt’s accounts survived as backing to a cartulary belonging to the Waley family, The problem is that the various accounts from the household rolls have been rather badly damaged when they were reused. The National Archives explains that the accounts list members of the household and their daily allowance, expenses for various departments and cost of equine care. Bean uses figures from Gaunt’s financial returns to calculate that at the time of his death there were approximately two hundred knights and squires in his retinue. Apparently squires were paid 10 marks a year whilst a basic knight’s salary was £20. Bean goes on to provide a handy appendices listing all of Gaunt’s knights. John Neville of Raby is the first one of the list as was Lord Welles and Sir John Marmion. The Camden Society also have a list of Gaunt’s retainers written by Lodge and Sommerville and Walker’s Lancaster Affinity is a useful text.

The more I read though, the more it became clear that the indentures were a business arrangement and whilst a number of men are consistently in Gaunt’s household many of them appear for a brief time only. This is best explained as a military arrangement rather than a matter of feudal duty. The men who fought for John during one season might re-enlist in another magnate’s retinue for the next season’s fighting in France. The idea of the retinue is much more complicated than it first appears. It is not just about feudal links and tenure of land. There are political and financial considerations to be taken on board as well as gaining a foothold in the household of England’s wealthiest magnate. Sir John Saville of West Yorkshire is a relatively straightforward example of fealty. He fought for Henry Duke of Lancaster (Blanche of Lancaster’s father) and then turns up in Gaunt’s retinue in Spain. He’s also one of those parliamentarians with a Lancastrian affinity mentioned at the start of this post. Saville’s loyalty to the house of Lancaster is confirmed by the fact that the chantry at Elland built at the end of the fourteenth century was for prayers not just for the Saville family but also for the dukes of Lancaster. However, just to throw a small spanner in the wheel, Sir John also turns up in the records as doing service in the retinue of the Black Prince in the mid 1350’s demonstrating that membership of a martial retinue was not always about feudal duty or loyalty to a particular family.

Walker demonstrates throughout his book that during the fourteenth century feudalism was not always what is taught in school – even taking the effects of the Black Death into consideration. Knights and lords were not necessarily obedient to the will of their overlords. Independent action occurs as demonstrated by the number of men shifting from one retinue to another during campaigns in France. Walker also gives examples of men at the heart of Lancastrian territories acting contrary to Gaunt’s will – suggesting that society was much more complicated in the fourteenth century than text books often credit.

Armitage-Smith, Sydney. (1937) John of Gaunt’s Register Camden Society, 3rd series, LVI-LVII https://archive.org/details/gauntsregister01smituoft (accessed 22.00 16/07/2017)

Bean, John Malcolm William. (1989) From Lord to Patron: Lordship in Late Medieval England. Manchester: Manchester University Press

E.C. Lodge and R. Somerville (ed) John of Gaunt’s Register, 1372–1376

Walker, Simon. (1990) The Lancaster Affinity: 1361-1399. Oxford: Oxford Historical Monographs

now that is impressive work.Enjoyed reading it. As in any club rules change as time travels on. I did think that one could serve any master who paid well even in the early days of William Duke of Normandy. Looking at your radical view one comes to join your thoughts it is far more complex than we have been led to believe.Perhaps more on this subject can fit the bill from you. Thank you for it.

Glad you’re enjoying it – not sure where I’ll progress with the retinue but there’s plenty to get my teeth into, including some familiar names.