Even before the Civil war started various key ports and fortifications were being snaffled either by Parliament or the Crown. Some, like Bristol and Lichfield, changed hands more than once inflicting severe damage on the local populations.

Even before the Civil war started various key ports and fortifications were being snaffled either by Parliament or the Crown. Some, like Bristol and Lichfield, changed hands more than once inflicting severe damage on the local populations.

Chester sitting as it does on the River Dee was one of those strategic locations. It gave access to Wales, to Ireland and to the North. It was also Royalist in sympathy. Before the war it was a very fine town indeed. After the civil war, the siege and the plague which struck in 1647 it looked very much worse for wear.

By the end of 1643 Sir William Brereton (pictured right) who had been one of the MPs for Cheshire and been elected in 1640 to the Long Parliament had secured most of the surrounding countryside for Parliament. The Royalists extended Chester’s defences to include new earthworks recognising that their time would come. In 1644 those defences were improved by Prince Rupert – who seems to have got everywhere.

By the end of 1643 Sir William Brereton (pictured right) who had been one of the MPs for Cheshire and been elected in 1640 to the Long Parliament had secured most of the surrounding countryside for Parliament. The Royalists extended Chester’s defences to include new earthworks recognising that their time would come. In 1644 those defences were improved by Prince Rupert – who seems to have got everywhere.

Rupert, had been named President of Wales in February 1644 but very swiftly irritated the local military commanders – mainly because he replaced them with experienced English commanders. The Welsh, unsurprisingly, were also becoming a bit fed up with the war. Rupert, having rocked the metaphorical boat left the region with rather a lot of its soldiery to lift the siege at York.

Parliament took the opportunity to gain an advantage over the depleted Royalist troops and took Oswestry which had, until then, been in Royalist hands. As the year went on things became even worse for the Royalists. A shipment of gunpowder on its way to Chester from Bristol was captured. The gunpowder was then used against the Royalists at Newton. This in turn led to the loss of Montgomery Castle. On the 18th of September the two forces met in open battle. The Battle of Montgomery is the largest battle to have taken place on Welsh soil during the English Civil War. The Royalists lost.

As a result of this loss Lord John Byron, the Royalist military commander (pictured at the start of this post) could not put an army in the field and so Chester was effectively besieged. The Wheel of Fortune had turned in less than a year – from besieging Nantwich at the start of the year Byron now found himself besieged. By the summer of 1645 Brereton had control of most of Cheshire but the royalists still controlled the crossing point of the River Dee which enabled forces and supplies to get into and out of the town via North Wales which was Royalist.

Basically the siege was somewhat protracted by the fact that both sides kept nipping off to have a fight somewhere else. For example Prince Maurice, Rupert’s little brother, arrived in February 1645 but then left again taking a large number of Byron’s Irish troops with him.

With depleted numbers it was only a matter of time before the Parliamentarians drew closer to the town. There was also the bombardment. Byron wrote that Brereton had sent a barrage of 400 canon balls into Chester – which is pretty impressive. The original aim of the Parliamentary command had been to break the walls so that the town could be taken by storm. This proved ineffective and a tactic of bombardment was employed. There was widespread damage to property, injury and terror. On the 22nd September 1645 there was a partial breach of the wall but Byron received word that King Charles was coming with 4,000 cavalry.

On the 23 September Charles marched out of Wales and crossed the Dee into Chester – he had approximately 600 men. The rest of them were with Sir Marmaduke Langdale who crossed the Dee south of Chester with the intention of outflanking the Parliamentarians -making them the filling between his force and Byron’s.

Unfortunately the Northern Association Army were in the vicinity and upon receiving news of what the Royalists were up to had made a forced night march to intercept Langdale. The two armies spent the morning of the 24th September in a staring match before repositioning themselves at Rowton Heath. The king and his commanders inside Chester could do little but watch from the walls as the royalist cavalry was broken.

On the evening of the 25th September Charles recrossed the Dee with the tattered remnants of his relieving force. Byron refused to surrender. The Parliamentarian noose grew tighter around Chester and the bombardment became ever more intense. This didn’t stop Byron from trying to attack his besiegers on occasion.

When Chester did surrender it had more to do with starvation that the number of rounds of artillery fired at it. The mills and water supplies had been badly damaged by the bombardment. Lack of ammunition meant that the Royalists lost control of the crossing point and supplies could not enter the town.

Brereton shot propaganda leaflets across the walls to persuade the defenders to surrender but from October onwards there were no further attempts to breach the walls. Approximately 6000 people behind Chester’s walls were starving and diving of disease. It was just a question of waiting. By December 1645 the town’s defenders began to desert.

Chester’s mayor persuaded Byron to surrender in January 1646. The able bodied were allowed to leave whilst the sick and the starving were to be permitted an opportunity to recover. Brereton took possession of Chester on 3rd February 1646.

A quarter of Chester had been burned. What their artillery hadn’t destroyed the Parliamentarian soldiers now smashed.

Initially Brereton tried to take hold of Chester for Parliament but was unable to capture it. Instead having taken Nantwich for the Parliamentarian cause in 1642 he made that his headquarters. From there he ranged along the Welsh marches on Parliament’s behalf and down through Cheshire to Stafford. He came with Sir John Gell of Hopton in Derbyshire to the siege of Lichfield and was concerned at the later siege of Tutbury that his colleague was far too lenient on the Royalist defenders. Across the region Brereton was only defeated once at the Battle of Middlewich on December 26 1643 but he swiftly recovered from this as he had to return with Sir Thomas Fairfax to Nantwich when Sir George Booth managed to get himself besieged by Lord Byron and Cheshire was more or less completely in the hands of the Royalists not that this stopped Brereton from establishing an impressive network of spies loyal to Parliament.

Initially Brereton tried to take hold of Chester for Parliament but was unable to capture it. Instead having taken Nantwich for the Parliamentarian cause in 1642 he made that his headquarters. From there he ranged along the Welsh marches on Parliament’s behalf and down through Cheshire to Stafford. He came with Sir John Gell of Hopton in Derbyshire to the siege of Lichfield and was concerned at the later siege of Tutbury that his colleague was far too lenient on the Royalist defenders. Across the region Brereton was only defeated once at the Battle of Middlewich on December 26 1643 but he swiftly recovered from this as he had to return with Sir Thomas Fairfax to Nantwich when Sir George Booth managed to get himself besieged by Lord Byron and Cheshire was more or less completely in the hands of the Royalists not that this stopped Brereton from establishing an impressive network of spies loyal to Parliament. In January 1644 Sir Thomas Fairfax crossed the Pennines with men from the Eastern Association Army. On the 25th January his men were met by a Royalist army headed by Byron who was defeated. The place where the two armies collided was Necton but the disaster for the royalists has become known in history as the Battle of Nantwich. It meant that the king could not hold the NorthWest. Even worse Royalist artillery and senior commanders were captured along with the baggage train. None of this did any harm to Sir Thomas Fairfax’s reputation nor to Brereton who had command of the Parliamentarian vanguard.

In January 1644 Sir Thomas Fairfax crossed the Pennines with men from the Eastern Association Army. On the 25th January his men were met by a Royalist army headed by Byron who was defeated. The place where the two armies collided was Necton but the disaster for the royalists has become known in history as the Battle of Nantwich. It meant that the king could not hold the NorthWest. Even worse Royalist artillery and senior commanders were captured along with the baggage train. None of this did any harm to Sir Thomas Fairfax’s reputation nor to Brereton who had command of the Parliamentarian vanguard. From there Brereton became involved in the siege of Chester – at Nantwich Byron had been outside the town whilst at Chester he was inside the walls. In September 1645 Bristol in the command of Prince Rupert surrendered. The only remaining safe harbour to land troops loyal to the king was Chester. Lord Byron had withdrawn there following his defeat at Nantwich and Brereton had followed him. Byron held the river crossing and in so doing was denying the Parliamentarians a way into North Wales which was Royalist.

From there Brereton became involved in the siege of Chester – at Nantwich Byron had been outside the town whilst at Chester he was inside the walls. In September 1645 Bristol in the command of Prince Rupert surrendered. The only remaining safe harbour to land troops loyal to the king was Chester. Lord Byron had withdrawn there following his defeat at Nantwich and Brereton had followed him. Byron held the river crossing and in so doing was denying the Parliamentarians a way into North Wales which was Royalist. As with all civil wars some people change their minds. Having described the Hothams (father and son) shutting the city gates of Hull in Charles I’s face in 1642 it comes as something of a surprise to discover that John Hotham (junior) was executed for treason on 1st January 1645 for conspiring to let the royalists in! John Hotham senior was executed the next day. Unfortunately for them their coat turning tendencies had been proved by the capture of the Earl of Newcastle’s correspondence after the Battle of Marston Moor.

As with all civil wars some people change their minds. Having described the Hothams (father and son) shutting the city gates of Hull in Charles I’s face in 1642 it comes as something of a surprise to discover that John Hotham (junior) was executed for treason on 1st January 1645 for conspiring to let the royalists in! John Hotham senior was executed the next day. Unfortunately for them their coat turning tendencies had been proved by the capture of the Earl of Newcastle’s correspondence after the Battle of Marston Moor.

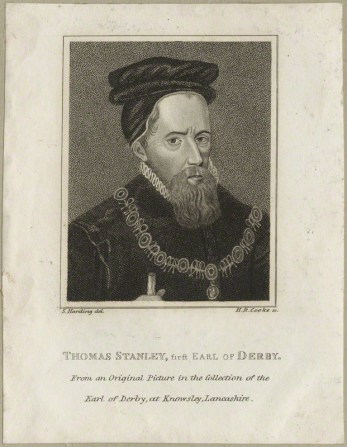

Thomas Stanley is known either as a politically adroit magnate who successfully navigated the stormy seas of the Wars of the Roses or a treacherous little so-and-so – depending upon your historical view point. Stanley is the bloke married to Margaret Beaufort who is best known for being a tad tardy at Bosworth whilst his brother, Sir William, turned coat and attacked Richard III. Stanley wasn’t the only one whose behaviour during the various battles of the wars seems lacking in the essential codes of knightly behaviour but he certainly seems to have been the most successful at avoiding actually coming to blows with anyone unless there was something in it for him – and no this post is not unbiased.

Thomas Stanley is known either as a politically adroit magnate who successfully navigated the stormy seas of the Wars of the Roses or a treacherous little so-and-so – depending upon your historical view point. Stanley is the bloke married to Margaret Beaufort who is best known for being a tad tardy at Bosworth whilst his brother, Sir William, turned coat and attacked Richard III. Stanley wasn’t the only one whose behaviour during the various battles of the wars seems lacking in the essential codes of knightly behaviour but he certainly seems to have been the most successful at avoiding actually coming to blows with anyone unless there was something in it for him – and no this post is not unbiased. Lichfield, in pre-Conquest times was a great see covering most of Mercia, these days its very much smaller and well worth a visit with its beautiful gospels and carved angel.

Lichfield, in pre-Conquest times was a great see covering most of Mercia, these days its very much smaller and well worth a visit with its beautiful gospels and carved angel.