I’ve blogged about Henry Tudor’s mother before and am always surprised at the reaction she seems to provoke including that it’s obvious that she was responsible for the murder of the princes – by which people do not mean that she was stalking the corridors of the Tower of London beating small boys to death with her psalter but that she “must” have reached an accommodation with the Duke of Buckingham who she was seen talking with during a “chance encounter” on the road prior to the rebellion which led to his execution (and he was family after all) in 1483. I have also been accused of being biased against her as well as biased in her favour in the same post. To which my response was – eh?

I’ve blogged about Henry Tudor’s mother before and am always surprised at the reaction she seems to provoke including that it’s obvious that she was responsible for the murder of the princes – by which people do not mean that she was stalking the corridors of the Tower of London beating small boys to death with her psalter but that she “must” have reached an accommodation with the Duke of Buckingham who she was seen talking with during a “chance encounter” on the road prior to the rebellion which led to his execution (and he was family after all) in 1483. I have also been accused of being biased against her as well as biased in her favour in the same post. To which my response was – eh?

The main problem for Margaret would seem to be the question – Who gains? And quite obviously, her son Henry Tudor became king of England. Couple that with means, motive and opportunity and Margaret Beaufort has to be included on the suspect list -she was after all Lady Stanley by this point and had a prominent position at court until she blotted her copy books and found herself under house arrest. Even if she didn’t have access to the Tower, the Duke of Buckingham did and Lord Stanley was part of Richard III’s circle of power (though not part of the inner circle.) Everyone in power or with money had access to the kind of men who would kill children – even women if they had trusted servants. It was not until Josephine Tey’s wonderful book entitled The Daughter of Time which was published in 1951 that anyone pointed the finger at Margaret although there had been doubts about Richard III’s involvement for centuries.

Henry Tudor didn’t launch an inquiry to find out what had happened in 1485 – nor was there any religious rite for the pair of princes which seems odd given that he had to revoke their illegitimacy in order to marry their sister Elizabeth – so it would have been only polite to mark their demise. But then who wants to draw attention to their presumed dead and now legitimate brothers-in-law and the fact that your own claim to the throne is a tad on the dodgy side? Edward IV didn’t want Henry VI turning into a cult so why would Henry Tudor want Edward V turning into a cult? And there is also the fact that having a mass said for the souls of the dead is one thing but what if one or more of the boys was still alive – it would be a bit like praying for their immediate death. Which brings us to Perkin Warbeck. Or was he? No wonder the story continues to fascinate people and excite so much comment.

However, back to Margaret Beaufort and the point of today’s post. Strong women in history often get a bad press both during their life times and in the history books – assuming they manage to get out of the footnotes because until fairly recently history was written from a male perspective – and Victorian minded males at that – women were supposed to be domestic and pious, they were not supposed to step out from the hearth and engage in masculine activities nor were they supposed to be intellectually able (the notable exception to this rule being Elizabeth I.)

Margaret Beaufort began life as a typical heiress – tainted by the apparent suicide of her father the Duke of Somerset- Once her father died she was handed over to a guardian, in this case the Duke of Suffolk. Suffolk effectively gained control of Margaret’s wealth and also had the power to arrange her marriage – which he duly did – to his own son John de la Pole. This marriage would be dissolved before Margaret left childhood. Margaret never considered herself to have been married to John. The fact that it was dissolved on the orders of no less a person than Henry VI demonstrates that she was a pawn on a chess board – just as most other heiresses were at this time. There was also her links to the Lancastrian bloodline to be considered. Her great grandparents were John of Gaunt and Katherine Swynford (and no I’m not exploring the legitimacy of the legitimisation of their family in this post) but at the time of her marriage to Tudor there were male Beauforts available who would have taken precedence in such matters. Margaret was also descended from Edward I via her maternal grandmother Lady Margaret Holland but that’s neither here nor there for the purposes of this post other than to note it was another source of Margaret Beaufort’s wealth.

Her lot was to marry and produce children. To this end Henry VI arranged a marriage between Margaret and his own half-brother Edmund Tudor who he had created Earl of Richmond but who now needed the money to go with the title. When the pair married on 1st November 1455, she was twelve. Edmund was twenty-four. By the following year Margaret was a widow and two months after that a mother. Let’s not put modern morality on Edmund’s actions. Had Margaret died before she became a parent her estates and income would have reverted to her family rather than to her husband. It was in Edmund’s financial interests to begin married life as soon as possible. It is probably for this reason that Edmund chose not to defer consummation until Margaret had matured somewhat.

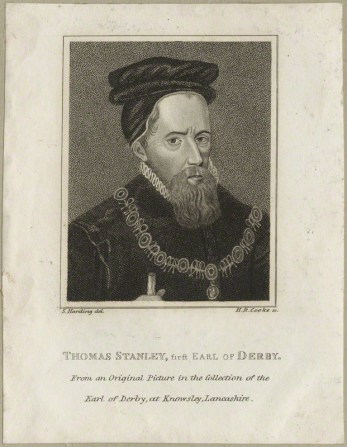

In March 1457 Margaret married for a second time (or third if you’re being pedantic) to the Duke of Buckingham’s second son- Henry Stafford. This was a marriage that had been negotiated by Margaret’s mother Margaret Beauchamp of Bletsoe. Jasper Tudor may also have been involved as he escorted Margaret from Pembroke and had his own financial interests to consider. The Duke of Buckingham (pictured left) was a powerful political ally in that he was as powerful as Richard of York (pictured right).

In March 1457 Margaret married for a second time (or third if you’re being pedantic) to the Duke of Buckingham’s second son- Henry Stafford. This was a marriage that had been negotiated by Margaret’s mother Margaret Beauchamp of Bletsoe. Jasper Tudor may also have been involved as he escorted Margaret from Pembroke and had his own financial interests to consider. The Duke of Buckingham (pictured left) was a powerful political ally in that he was as powerful as Richard of York (pictured right). It was a marriage that would protect Margaret’s interests but which would separate her from her son who was now in the guardianship of Jasper Tudor, the Earl of Pembroke. After the Battle of Towton in 1461 young Henry would be placed in the care of the Yorkist Herbert family. Margaret would never have another child – even if she could visit this one on occasion whilst he was resident with the Herberts before he and Uncle Jasper fled across The Channel in 1471 following the short-lived second reign of Henry VI.

It was a marriage that would protect Margaret’s interests but which would separate her from her son who was now in the guardianship of Jasper Tudor, the Earl of Pembroke. After the Battle of Towton in 1461 young Henry would be placed in the care of the Yorkist Herbert family. Margaret would never have another child – even if she could visit this one on occasion whilst he was resident with the Herberts before he and Uncle Jasper fled across The Channel in 1471 following the short-lived second reign of Henry VI.

It was during this marriage that Margaret Beaufort began to develop the skills that would help her son to the throne. Sir Henry Stafford, was a third cousin and some eighteen years older than her. Although he was a Lancastrian and fought on the loosing side at Towton he soon sued for pardon. During the 1460s Sir Henry rose in the Yorkist court. He demonstrated the necessity of being politically realistic. In 1468 Margaret and her husband entertained Edward IV at their hunting lodge near Guildford. For whatever reason Sir Henry fought against the Lancastrians at the Battle of Barnet and eventually died of the wounds he received there. Pragmatism would see Margaret into another marriage and into a role at the courts of Edward IV and Richard III.

Margaret, rather like the redoubtable Tudor Bess of Hardwick, had a very businesslike approach to marriage – as is demonstrated by her marriage to Thomas Stanley. Bess married for money whilst Margaret married for security, access to a power base, and, it would appear, for the chance to bring her son safely home from exile. Who can blame her? She been married off twice in her childhood due to her wealth and family links. The man she regarded as her first husband, Edmund Tudor, had died whilst in the custody of his enemies albeit from plague. Her second husband had relinquished his Lancastrian loyalties demonstrating real-politic and then died of wounds sustained in one of the intermittent battles of the period. Why would Margaret not marry someone close to the seat of power who could keep her, her inheritance and potentially her son safe? The fact that she married only eight months after the death of Sir Henry Stafford is not suggestive of undue haste, rather a desire to ensure that she had a role in the decision making.

The other thing that Margaret learned during her time as Lady Stafford was the importance of loyal servants not to mention a network of contacts. Reginald Bray began his career as Sir Henry’s man but would go on to become Margaret’s man of business, trusted messenger and ultimately adviser to Henry Tudor. So far as the contacts are concerned she had an extended family through her mother’s various marriages and her own marriages. As a woman of power i.e. Lady Stanley she had influence at court. She knew people and it would appear from Fisher’s biography had a capacity for getting on with them (not something that modern fictional presentations tend to linger on.)

In 1483 Margaret was heavily involved in the Duke of Buckingham’s rebellion against Richard III. Her agent was Reginald Bray. Polydore Virgil – the Tudor historian- made much of Margaret’s role at this time. During the reign of Edward IV she had petitioned for Henry’s return home as the Earl of Richmond now, in the reign of Richard III, she plotted to make her son king. She arrived at an accommodation with Elizabeth Woodville so that Princess Elizabeth of York would become Henry’s wife – making it quite clear that by this point Elizabeth Woodville believed her sons to be dead. Autumn storms caused Henry’s boats to turn back before the rebellion ended in disaster but he swore that he would marry Elizabeth of York. Not only would such a marriage reunite the two houses of Lancaster and York but it would legitimise Henry as king – should the situation arise. Pragmatic or what?

As a result of her involvement with the 1483 plot Margaret found herself under house arrest and all her property in the hands of her husband. Her wealth wasn’t totally lost and Lord Stanley connived to allow her continued communication with her son. Margaret was no longer a pawn on the chess board she had become an active player – and furthermore knew how to play the various pieces to best advantage and to hold her nerve.

There is popular acceptance of men such as Edward IV and the Earl of Warwick – politics and violence in the fifteenth century were suitably manly pastimes. It was an era when “good” men did “bad” things to maintain stability. We know that Edward must have ordered the murder of Henry VI following the Battle of Tewkesbury but he has not been vilified for it – you can’t really have two kings in one country without the constant fear of civil war. He ordered his own brother’s execution – but again he is not vilified for it – after all George Duke of Clarence had changed sides more often than he’d changed his underwear by that point.

By contrast Margaret Beaufort, despite Fisher’s hagiography, has not always been kindly portrayed in recent years – words like “calculating” are hardly positive when it comes to considering the child bride who became a kingmaker thanks to her own marriages and her negotiations with Elizabeth Woodville. Come to think of it Bess of Hardwick has had more than her share of bad press in the past as have women like Elizabeth Woodville and Henry VI’s queen Margaret of Anjou. Ambitious women, whether for power or money, were not and are still not treated kindly by posterity – possibly because they stepped out of their allotted role and refused to behave as footnotes.

DO I think she did it? In all honesty? I don’t know but probably not. I don’t have any evidence that says she did and neither does anyone else. I would also politely point out that she did not have custody of the two princes nor was she responsible for their safety. Did she benefit from their deaths – yes- but she would have been a fool not to and no one has ever accused Lady Margaret Beaufort of being one of those. There were plenty of other people who could have arranged their deaths and been on the scene to benefit much faster than Henry Tudor who was in Brittany at the time. But as I said at the start of the post people do feel strongly on the subject – here’s a picture to give you a flavour.

https://www.royalhistorygeeks.com/why-margaret-beaufort-could-not-have-killed-the-princes-in-the-tower/ It’s worth looking at the comments -for every argument made in the History Geek post there is a counter argument. For those of you who want to see the argument that she could have had the princes killed go to: https://mattlewisauthor.wordpress.com/2016/09/04/margaret-beaufort-and-the-princes-in-the-tower/

I shall be talking to the U3A Burton-On-Trent, Rolleston Club on 27th February at 10.00 am on the topic of Lady Margaret Beaufort. There’re bound to be questions!

Licence, Amy. 2016 Red Roses. Stroud: The History Press

Jones, Michael and Underwood, Malcom. (1992) The King’s Mother. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Thomas Stanley is known either as a politically adroit magnate who successfully navigated the stormy seas of the Wars of the Roses or a treacherous little so-and-so – depending upon your historical view point. Stanley is the bloke married to Margaret Beaufort who is best known for being a tad tardy at Bosworth whilst his brother, Sir William, turned coat and attacked Richard III. Stanley wasn’t the only one whose behaviour during the various battles of the wars seems lacking in the essential codes of knightly behaviour but he certainly seems to have been the most successful at avoiding actually coming to blows with anyone unless there was something in it for him – and no this post is not unbiased.

Thomas Stanley is known either as a politically adroit magnate who successfully navigated the stormy seas of the Wars of the Roses or a treacherous little so-and-so – depending upon your historical view point. Stanley is the bloke married to Margaret Beaufort who is best known for being a tad tardy at Bosworth whilst his brother, Sir William, turned coat and attacked Richard III. Stanley wasn’t the only one whose behaviour during the various battles of the wars seems lacking in the essential codes of knightly behaviour but he certainly seems to have been the most successful at avoiding actually coming to blows with anyone unless there was something in it for him – and no this post is not unbiased. The Benedictine nunnery of King’s Mead in Derby dedicated to the Virgin Mary was the only Benedictine foundation in Derbyshire and its inhabitants were initially under the spiritual and temporal guidance of the abbot of Darley Abbey – an Augustinian foundation. History reveals that in the twelfth century there was a warden who acted as chaplain to the nuns as well as looking after the nuns’ business affairs. The nunnery grew its land holdings over the next hundred or so years so that it included three mills at Oddebrook. One of the reasons that this may have occurs was because Henry III gave the nuns twelve acres of land. Because the king had shown an interest it is possible that more donors followed suit in an effort to win favour. Equally donors such as Lancelin Fitzlancelin and his wife Avice who gave land and animals to the nunnery in 1230 or Henry de Doniston and his wife Eleanor could expect a shorter term in Pergatory after their deaths because the nuns would be expected to hold them in their prayers as a result of the land transaction.

The Benedictine nunnery of King’s Mead in Derby dedicated to the Virgin Mary was the only Benedictine foundation in Derbyshire and its inhabitants were initially under the spiritual and temporal guidance of the abbot of Darley Abbey – an Augustinian foundation. History reveals that in the twelfth century there was a warden who acted as chaplain to the nuns as well as looking after the nuns’ business affairs. The nunnery grew its land holdings over the next hundred or so years so that it included three mills at Oddebrook. One of the reasons that this may have occurs was because Henry III gave the nuns twelve acres of land. Because the king had shown an interest it is possible that more donors followed suit in an effort to win favour. Equally donors such as Lancelin Fitzlancelin and his wife Avice who gave land and animals to the nunnery in 1230 or Henry de Doniston and his wife Eleanor could expect a shorter term in Pergatory after their deaths because the nuns would be expected to hold them in their prayers as a result of the land transaction.