According to the Scotsman Berwick Upon Tweed changed hands some thirteen times in its turbulent history. So, it was originally part of the Kingdom of Northumbria and these are the key changes of occupier.

According to the Scotsman Berwick Upon Tweed changed hands some thirteen times in its turbulent history. So, it was originally part of the Kingdom of Northumbria and these are the key changes of occupier.

In 1018 following the Battle of Carham the border moved to the Tweed and Berwick became Scottish which it remained until William I of Scotland became involved in the civil war between Henry II and his sons in 1173. After his defeat Berwick became English. In all fairness Henry II had rather caused bad feeling between the Scots and English when he forced the Scots to hand Carlisle back to England – which given how supportive King David of Scotland had been to him seems rather ungracious. William I of Scotland (or William the Lion if you prefer) had simply taken advantage of the family fall out between Henry II and his sons. Unfortunately for him he was captured in 1174 at the Battle of Alnwick. He was released under terms of vassalage and made to give up various castles as well as Berwick.

In 1018 following the Battle of Carham the border moved to the Tweed and Berwick became Scottish which it remained until William I of Scotland became involved in the civil war between Henry II and his sons in 1173. After his defeat Berwick became English. In all fairness Henry II had rather caused bad feeling between the Scots and English when he forced the Scots to hand Carlisle back to England – which given how supportive King David of Scotland had been to him seems rather ungracious. William I of Scotland (or William the Lion if you prefer) had simply taken advantage of the family fall out between Henry II and his sons. Unfortunately for him he was captured in 1174 at the Battle of Alnwick. He was released under terms of vassalage and made to give up various castles as well as Berwick.

Henry II’s son, Richard the Lionheart, who, as I have mentioned previously, would have been more than prepared to sell London to the highest bidder to finance his Crusade sold the town back to the Scots where it remained until 1296 and the Scottish Wars of Independence. Needless to say it was Edward I who captured the town for the English at that time after the Scots had invaded Cumberland under the leadership of John Baliol who was in alliance with the French. There were executions and much swearing of fealty not to mention fortification building.

Henry II’s son, Richard the Lionheart, who, as I have mentioned previously, would have been more than prepared to sell London to the highest bidder to finance his Crusade sold the town back to the Scots where it remained until 1296 and the Scottish Wars of Independence. Needless to say it was Edward I who captured the town for the English at that time after the Scots had invaded Cumberland under the leadership of John Baliol who was in alliance with the French. There were executions and much swearing of fealty not to mention fortification building.

In April 1318 during the reign of Edward II (who was not known for his military prowess) Berwick fell once again to the Scots. By 1333 the boot was on the other foot with Edward III now on the throne. Sir Archibald Douglas found himself inside the town and preparing for a siege – no doubt making good use of the fortifications built on the orders of Edward I. Douglas was defeated at the Battle of Halidon Hill in September 1333 and Berwick became English once more.

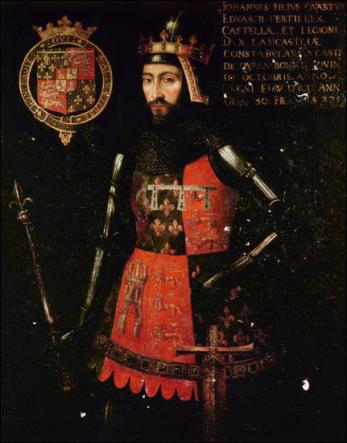

And thus it might have remained but for the Wars of the Roses. In 1461 Edward IV won the Battle of Towton leaving Henry VI without a kingdom. Margaret of Anjou gave Berwick and Carlisle to the Scots in return for their support to help when the Crown once again. I should point out that the citizens of Carlisle did not hand themselves over to Scotland whilst those in Berwick found themselves once more under Scottish rule. Not that it did Margaret of Anjou much good nor for that matter diplomatic relations between Scotland and the new Yorkist regime although there was a treaty negotiated in 1474 which should have seen 45 years of peace – as all important treaties were this one was sealed with the agreement that Edward’s third daughter Cecily should marry James III’s son also called James. Sadly no one appears to have told anyone along the borders of this intent for peaceful living as the borderers simply carried on as usual.

August 24 1482 Berwick became English once more having fallen into the hands of Richard, Duke of Gloucester who strengthened his army with assorted European mercenaries until there were somewhere in the region of 20,000 men in his force. Richard marched north from York in the middle of July. Once at Berwick Richard left some men to besiege the town whilst he went on to Edinburgh where he hoped to meet with King James III of Scotland in battle (it should be noted that one of James’ brothers was in the English army). It wasn’t just James’ brother who was disgruntled. It turned out that quite a few of his nobles were less than happy as they took the opportunity of the English invasion to lock James away. It became swiftly clear to Richard that he would not be able to capture Edinburgh so returned to Berwick where he captured the town making the thirteenth and final change of hands.

August 24 1482 Berwick became English once more having fallen into the hands of Richard, Duke of Gloucester who strengthened his army with assorted European mercenaries until there were somewhere in the region of 20,000 men in his force. Richard marched north from York in the middle of July. Once at Berwick Richard left some men to besiege the town whilst he went on to Edinburgh where he hoped to meet with King James III of Scotland in battle (it should be noted that one of James’ brothers was in the English army). It wasn’t just James’ brother who was disgruntled. It turned out that quite a few of his nobles were less than happy as they took the opportunity of the English invasion to lock James away. It became swiftly clear to Richard that he would not be able to capture Edinburgh so returned to Berwick where he captured the town making the thirteenth and final change of hands.

Meanwhile the Scottish nobility asked for a marriage between James’ son James and Edward IV’s daughter Cecily to go ahead. Richard said that the marriage should go ahead if Edward wished it but demanded the return of Cecily’s dowry which had already been paid.

Just to complicate things – James’ brother, the one fighting in the English army proposed that it should be him that married Cecily. He had hopes of becoming King himself. Edward IV considered the Duke of Albany’s proposal and it did seem in 1482 that there might be an Anglo-Scottish marriage but in reality the whole notion was unpopular. The following year, on 9th April, Edward died unexpectedly and rather than marrying royalty Cecily found herself married off to one of her uncle’s supporters Ralph Scrope of Masham. This prevented her from being used as a stepping-stone to the Crown. This particular marriage was annulled by Henry VII after Bosworth which occurred on 22 August 1485 and Cecily was married off to Lord Welles who was Margaret Beaufort’s half-brother and prevented Cecily, once again, from being used as a stepping-stone to the Crown.

Meanwhile Berwick remained relatively peacefully until 1639 when the Scottish Presbyterian Army and Charles I’s army found itself at a standoff. The Pacification of Berwick brought the so-called First Bishops’ War to an end. Unsurprisingly Charles broke the agreement just as soon as he had gathered sufficient funds, arms and men. The Second Bishops’ war broke out the following year with the English Civil War beginning in 1642.

The Katherine Swynford Society runs two quarterly writing competitions – one biographical the other fictional. Their website states that:

The Katherine Swynford Society runs two quarterly writing competitions – one biographical the other fictional. Their website states that: Baron Lionel de Welles was born in 1406. The family was a Lincolnshire one but Lionel’s mother was the daughter of Lord Greystoke (pause for Tarzan jokes if you wish).

Baron Lionel de Welles was born in 1406. The family was a Lincolnshire one but Lionel’s mother was the daughter of Lord Greystoke (pause for Tarzan jokes if you wish).